It’s been just over eight months since our last technical deep dive into TEFCA Individual Access Services (IAS). In earlier posts, we looked broadly at the issues shaping TEFCA’s rollout—from inconsistent OIDC claims to governance gaps and the operational realities of cross-network exchange. This time, we’re narrowing the scope.

This article focuses on one of the most fundamental yet least understood parts of TEFCA IAS: Patient Matching Algorithms and Record Locator Services (RLS). These systems sit at the heart of how data is found and shared across networks, but they also introduce some of the most persistent problems in interoperability.

Before we get into how TEFCA IAS handles identity and record discovery, it’s worth revisiting how patient matching works in healthcare today, and why the U.S. still struggles with something as basic as knowing which “John Doe” a healthcare provider is actually treating.

National Identification Numbers & Patient Matching

While some countries have a concept of a National Identification Number that can be used to uniquely identify a patient across healthcare providers, that concept does not exist in the US. There’s actually a longstanding federal ban that prevents the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) from using federal funds to create a national, unique patient identifier – commonly referred to as Section 510

Sec. 510 “None of the funds made available in this act may be used to promulgate or adopt any final standard … providing for, or providing for the assignment of, a unique health identifier for an individual (except in an individual’s capacity as an employer or a health care provider), until legislation is enacted specifically approving the standard.”

This ban has broad second-order effects, but let’s stay focused on what this means for HIEs and TEFCA.

National Health Information Exchanges (HIEs) are responsible for exchanging over 1 Billion Medical Records a month. HIEs are made up of healthcare organizations that are (usually) exchanging records for treatment. This means there’s a provider who is actively involved in caring for an individual patient, and as part of their treatment of that individual, they require a copy of the patient’s historical information.

They can get this medical history by “querying” the network: asking each of the other healthcare organizations on the network, “Do you have records for this patient?” and then stitching those responses together into a “comprehensive” medical record.

Any engineer will tell you: the fastest and most accurate way to query a large dataset is with a unique ID. But, as discussed above, the US doesn’t allow a national patient identifier.

So what’s the next best thing? You might be thinking, “Can’t we just use a Social Security Number (SSN)?”.

Unfortunately, not. In the US, an SSN is more commonly used as a shared secret or a password, not a “username”. Banks and other sensitive institutions have been known to “verify” your identity with just the last 4 digits of your SSN. SSNs were never designed to be safe, portable, universal patient IDs. Using them for patient matching creates numerous security and fraud issues.

Patient Matching Algorithms

In reality, there’s no “right” answer here. So, we try to define a “unique” individual in other ways – using a combination of different factors. The goal is to narrow down to one person with high confidence.

A naive attempt might be something like “First Name” + “Last Name”, but “John Doe” is the almost universal counter-example.

Generally, you’ll find that most HIEs use some combination of the following factors, with different weighting for each.

- First name

- Last name

- Address / zip code

- Email Address

- Phone Number

- Birthdate

- Last 4 social

- Drivers license

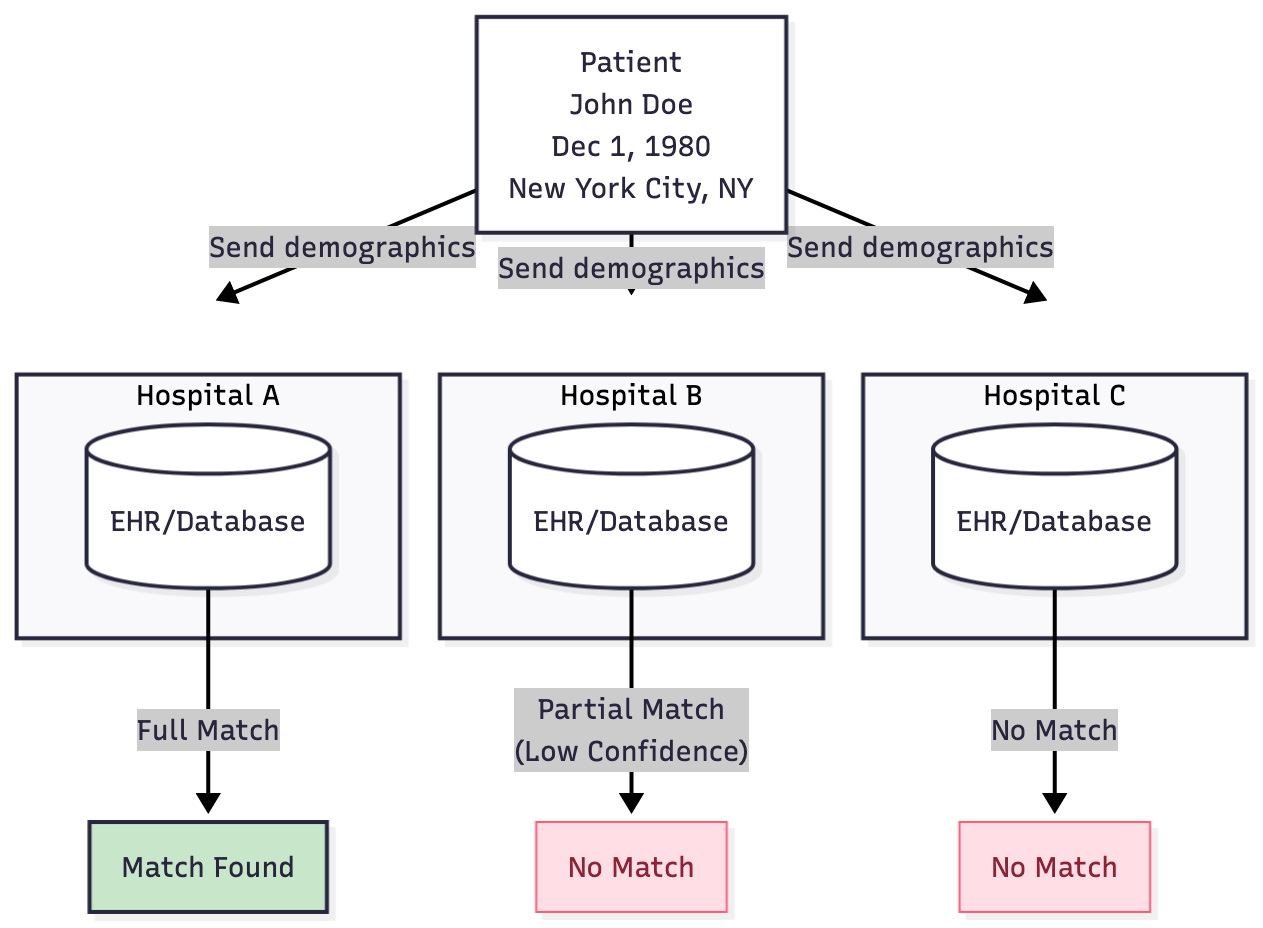

A healthcare provider on the network sends a query containing these demographics, asking the other institutions on the HIE network: Do you have any medical records for an individual who matches this combination of attributes?

This is the basis of a Patient Matching Algorithm.

What’s Wrong w/ Patient Matching Algorithms

Some of you may have already noticed the core problem with the demographic factors listed above.

- Many of the factors are not static over your lifetime. They can change.

- You can change your name. Example: maiden names, nicknames or shortened versions you use informally, or a legal name change.

- Your address will most likely change multiple times. Some individuals are unhoused and may not have a current address.

- Common names vs legal names

- Patients may have middle names that they do not usually share when filling out forms, but that appear in official records.

- Suffixes (Jr., PhD, etc.) and prefixes (Dr., Mr., Mrs.) may or may not be included when a provider or EHR user types your name into the chart.

- Some factors may not be available to all individuals:

- Not everyone has a driver’s license or a passport. As of 2024, approximately 169 million people lacked a passport and 30 million adults don’t have a drivers license

- Minors do not have driver’s licenses, but they still get sick and generate medical records.

- Mononyms are common in some cultures, and can be difficult to handle in a standardized way.

- Some factors are sensitive (eg, SSN, identified gender, address), and patients may not feel comfortable sharing them. This concern is justified given the frequency and scale of healthcare data breaches.

- Some factors are commonly misspelled or captured inconsistently, depending on dialect, accent, intake staff, or the storage structure within the EHR.

- Some factors are not commonly collected by providers. For example data governance policies at an institution may restrict the collection & use of certain information – similar to credit card numbers.

To “solve” these problems, responding healthcare organizations are generally stuck with permissive & complicated patient matching algorithms. They’ll accept a wide variety of data about the patient, weigh each factor differently, and calculate a confidence score for each possible match on their side.

They may also choose to customize their matching algorithm based on the data that they collect as part of intake forms, the socio-economic status of their patient population, and the EHR that they use. Some healthcare providers have chosen to treat their Patient Matching Algorithm as proprietary – which is understandable given the engineering effort required to tackle this complex problem.

There is no “Universal Patient Matching Algorithm”

Even worse, there’s no way to universally agree on an “acceptable” patient match confidence threshold. A “good enough” match threshold depends on the clinical context. While a 93.7% match might suffice for a prescription renewal, would it also be sufficient for surgery?

On the requesting side, healthcare organizations will also try to maximize the number of matches they receive by manipulating how they query:

- Multiple requests for each potential spelling or combination of a patient’s name

- Multiple requests for each historical address

It’s incredibly impressive that this works as well as it does – especially given the scale and importance of the data being exchanged.

Record Locator Service

As the number of nodes (providers) on a network grows, the number of requests needed to locate a patient’s record grows fast. It quickly becomes difficult to handle – especially when you take into account the number of “alternative” requests being made to handle historical addresses and names.

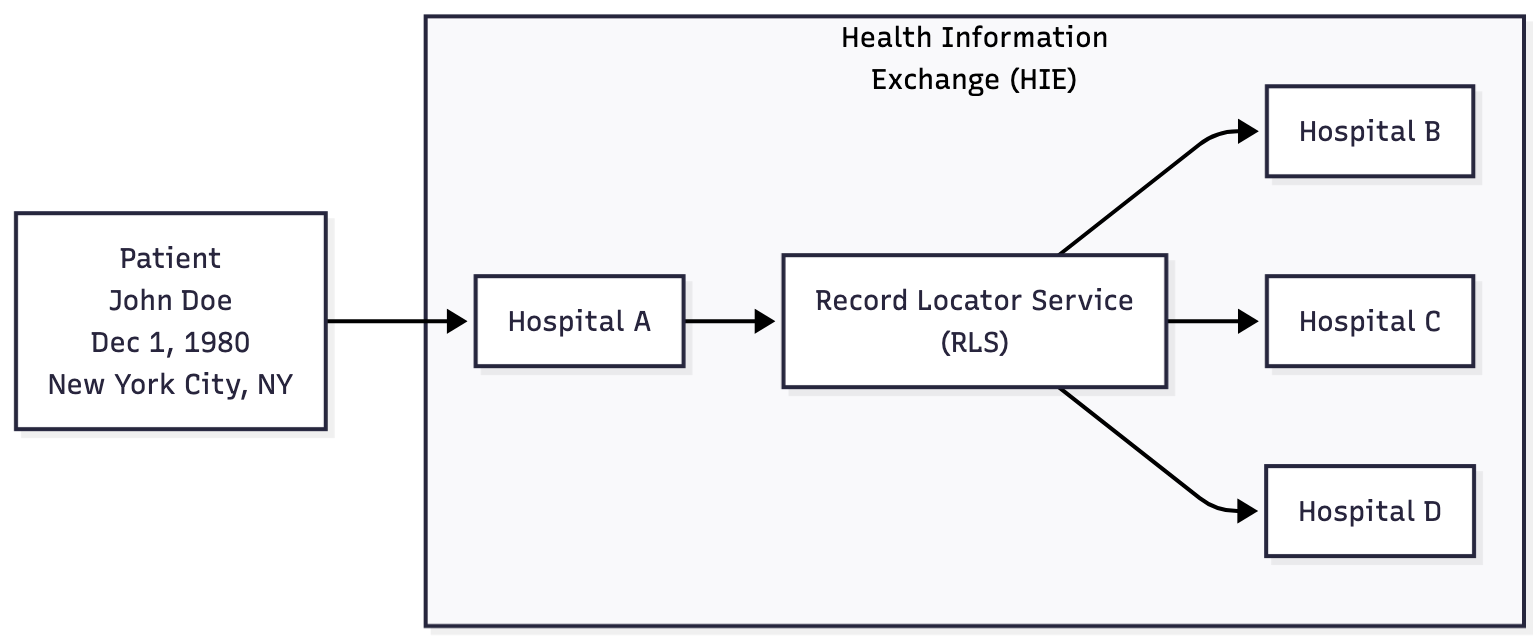

Many HIE networks address this by centralizing their patient query request/response service. They create a single Record Locator Service (RLS), which will usually contain a mapping of patient demographics to the various healthcare organizations within their network that hold the records for that individual.

When the query comes in, the RLS responds with “pointers” to the specific institutions that are likely to have the records. This lowers network congestion, but has a tradeoff of additional latency & eventual consistency.

Note, there are HIEs that do not have a centralized RLS – these decentralized networks think of themselves as “frameworks” instead, built upon a trust agreement. CareQuality & TEFCA fall into this latter category, commonly known as Health Information Networks (HINs). They use other techniques to mitigate network congestion – some of which are described below.

So What About TEFCA IAS?!

Ok, so what does this all have to do with TEFCA IAS?

Architecturally, you can still think of TEFCA as an HIE – or maybe a network of HIEs if you want to be more accurate. It’s still a simplification, but from the IAS Provider (Patient App) perspective, many of those other requirements are irrelevant to the discussion we’re having here.

Here is what you need to remember:

- Provider-to-provider queries still rely on an RLS and complex Patient Matching Algorithms

- TEFCA IAS layered a new use case on top of those same mechanics.

When the TEFCA Individual Access Services (IAS) SOP was added to the Common Agreement, it introduced a new mechanism that allows Patients to query for their own medical records from the network – piggybacking on the existing design & infrastructure already in use by Providers for record retrieval.

But IAS came with a number of additional technical requirements – the network needed a way to quickly and accurately confirm that “John Doe” is only requesting “John Doe’s” records, and not the records of a friend, family member, or celebrity.

Verifying that a real human is who they claim to be is a solved problem in other high-trust industries. The healthcare world borrowed the same approach, specifically NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-63A IAL2 Remote Identity Proofing

outlines requirements for digital identity enrollment and identity proofing. It specifies a high level of identity verification, requiring a combination of document-based proof, biometric data, and other methods to verify that a person is who they claim to be. This level is suitable for situations where the real-world existence and association of the identity must be confirmed with a high degree of confidence, such as in healthcare, government, and financial services*

The TEFCA IAS SOP offloads the responsibility of verifying the patient’s identity to a set of trusted third-party vendors – called Credential Service Providers (CSPs). You’ve probably used one before:

- CLEAR has 33 million members

- 152 million Americans have used ID.me

These CSPs generally verify the patient’s identity using a photo of their face (selfie) and a copy of their government-issued ID. They then send back a list of certified patient demographics that the IAS Provider app can use to make a query against the network & receive a response from the RLS.

This is what ensures that the records returned actually belong to the patient, not to someone else.

Problem #1 - Verified Demographics are Required

We’ve already talked about some of the common issues with CSPs in our previous article (non-standard OpenID Connect (OIDC) claims, token expiration), but let’s focus on the interaction between CSPs and patient matching.

Under TEFCA IAS, only patient demographics that have been validated and verified by the CSP can be used in a query. This is beneficial because it prevents impersonation, but it’s also a double-edged sword: the only demographics you are allowed to send are those that a CSP is capable of verifying.

That creates two immediate issues:

- None of the normal techniques that providers use to increase match rates on the network can be used by IAS apps.

- No nicknames

- No alternative spellings

- No historical addresses

- No historical names (for example maiden names)

- Anyone who does not have a government-issued ID will be completely blocked from making IAS requests. This impacts tens of millions of Americans and almost all minors.

Potential Solutions:

[ASTP / RCE]

- Define a TEFCA IAS attribute profile covering verified and historical demographics.

- Replace OIDC standard claims with OIDC-IDA (Identity Assurance Extension) claims, which supports additional flexibility, data fields & confidence scores

- Explore privacy-preserving national ID models under Section 510 limits.

- Modify the TEFCA IAS SOP to allow QHINs & EHRs to implement patient matching using both CSP-verified and patient-contributed data.

Problem #2 - Intended Use Mismatch

There is a growing mismatch between how TEFCA is used by providers and how TEFCA IAS is expected to be used by patients.

CareQuality & CommonWell have approximately 160k healthcare organizations on their networks

That number sounds big, it’s dwarfed by the number of individuals who could theoretically use an app to request their medical record from the TEFCA network. There are approximately. 360 million Americans. If just 5% decided to use an app to actively pull their records, that’s almost 18M patients querying the network on a semi-regular basis.

The network has historically been optimized for a Treatment purpose of use. Providers pull medical records on-demand while they are treating the patient. Once the patient is discharged or no longer actively managed by the provider, they are required to stop pulling data for that patient.

On the other hand, patients using a Personal Health Record (PHR) app will likely want a live copy of their medical records, forever. There are technical solutions for mitigating this (eg, moving from network polling to a notification-based workflow), but that doesn’t change the fact that patients are likely to be much more demanding of the network.

Patients will also expect a comprehensive, longitudinal record -- while providers may be satisfied with a partial record that is biased towards recent encounters.

Geofencing and Lookback Periods

This mismatch around intended use becomes clearer when you look at how some QHINs implement request filtering to minimize network query congestion and RLS usage. We’ve already observed two common techniques in the wild: Geofencing and Lookback Periods.

Geofencing refers to the use of virtual geographic boundaries to constrain or prioritize the search for patient records within specific regions or health information exchange (HIE) networks. Essentially, it acts as a digital perimeter—defined by zip codes, states, or organizational jurisdictions—that limits RLS queries to a set of healthcare entities most likely to hold relevant patient data. This approach improves query efficiency, reduces unnecessary network traffic, and strengthens privacy safeguards by ensuring that patient record searches occur only within authorized or contextually relevant areas

Epic Nexus is one of the TEFCA QHINs that has enabled Geofencing for RLS queries. If a patient has a verified address in NYC, then only NYC and nearby hospitals on Epic Nexus will be queried for the patient’s records.

Geofencing also affects provider requests, but (as mentioned earlier), providers have much more flexibility in how they construct their queries. They can send alternative spellings, historical addresses, and other permutations – IAS provider apps cannot. IAS provider apps are locked into CSP-verified demographics, which removes a patient’s ability to access a complete medical record, not just recent interactions near their current address.

A lookback period defines how far into the past a system searches for a patient’s records across participating organizations. It acts as a time filter, limiting queries to recent, relevant encounters

Some QHINs limit responses to a short lookback window. For example, Konza’s default setting only returns records from healthcare providers who have seen the patient within the past 12 months. That approach works reasonably well for providers who prioritize recent encounters, but for patients using personal health record apps, missing older data can be confusing and incomplete.

Potential Solutions:

[ASTP / RCE]

- Prohibit geofencing for IAS queries in TEFCA policy.

- Define minimum lookback standards for IAS responses (e.g., ≥5 years).

Problem 3: Liability Fears & Epic Nexus

Let’s loop back around to the lack of a National Patient Identifier, and its second-order effects.

Without a universal patient identifier, record queries have to include patient demographics. The responding health system runs its patient matching algorithm and returns what it thinks is the correct match. This matching is intrinsically confidence-based – there’s no way to guarantee perfect matches 100% of the time.

Some large, risk-averse healthcare organizations are uncomfortable with this, even though this is technically the exact same situation that already exists in HIEs today for provider-to-provider exchange. An incorrectly exchanged patient record is technically a HIPAA Breach – just classified as a “Low Probability of Compromise” – a category that IAS Provider applications could also fall under (see: the CARIN Alliance whitepaper: ==Individual Access Services on TEFCA and Wrong Record Scenarios==)

In any case, the result of this risk-aversion is that some QHINs, specifically Epic Nexus, put patients in a situation where TEFCA IAS is almost the worst of both-worlds: Epic Nexus still requires patients to authenticate through their health system’s portal, even after the network has already identified a patient match with high confidence. This is the exact workflow TEFCA IAS was designed to replace.

Potential Solutions:

[ASTP / RCE]

- Issue formal guidance confirming that properly mitigated wrong-record scenarios under IAS qualify as “Low Probability of Compromise (LoProCo).”

- Clarify the exact scenarious under which EHR vendors must respond to both RLS and Document requests – without additional authentication

[EHR Vendors]

- If an IAS Provider request includes a CSP verified patient identity, respond to both RLS and Document requests without any additional portal authentication step

- Implement identity harmonization between internal and external idPs. If a patient previously authenticated using a trusted CSP (Id.me, Clear, etc) and was able to login to their patient portal, associate this identifier with the patient’s account, such that future requests do not require patient portal login at all.

Problem 4: Implicit Consent & Lack of Authorization

When integrating with TEFCA IAS, one thing that IAS Providers will notice is the lack of an explicit consent process.

Again, this seems to trace back to how HIEs were designed. HIEs were intended to support record exchange between trusted parties. Under HIPAA, records requested for Treatment, Payment & Operations (TPO) by Covered Entities do not require explicit consent – even though some organizations still have the patient sign a HIE authorization form just in case.

Most requests on the HIE networks are tagged with “TREATMENT” (T-TRTMNT in TEFCA), meaning they are covered under HIPAA TPO, and are implicitly allowed – no consent required.

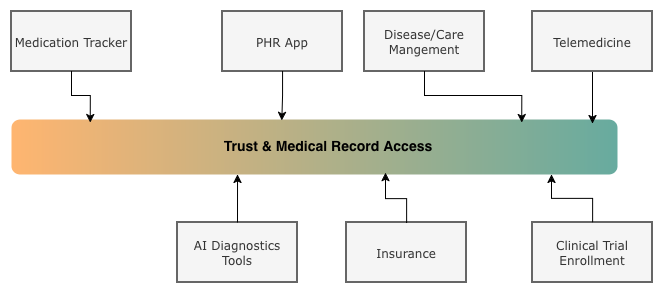

In the TEFCA IAS world, this trust model breaks down. Patients are allowed to request their own medical records, and participants of the TEFCA network are required to respond to T-IAS requests. The problem is that these records are not being sent directly to the patient – patients are giving their medical records to apps that they trust -- and that trust lives on a spectrum.

An app the patient just installed is not the same as a care management app they have used for years. Patients may want control over the types of records (and sensitive data) they share with an app. For example, behavioral health, reproductive health, genetic data, etc.

Unfortunately, the TEFCA IAS SOP does not require granular consent. Generally, there’s no way for a patient to say “share this part of my chart, but not that part.” It’s usually “all or nothing” – with the exception of Epic Nexus described above.

Yes, there are rules and regulations that apply to IAS apps (including rules around informed consent, the right to be forgotten and other protections), the catch-22 is that they still rely on the patient trusting the app, and the app doing the “right thing” after it already has the data.

Where does Authorization live?

There needs to be an authorization layer. The patient should be able to choose:

- What purposes are allowed for their medical records

- Which sources of records are allowed

- Which apps are allowed access

The problem is where to put this authorization layer. Since it can’t be at the App level (because of the catch-22 described above) there are only 2 other places it can be stored: the EHR / provider level, or the TEFCA network level.

Both of those approaches have problems.

It is debatable, but many EHRs and providers have a financial and operational disincentive to share medical records at all, especially with third-party apps. On the TEFCA side, a centralized consent service (as Josh Mandel has documented) could solve the problem, but is operationally complex and would require new shared infrastructure at QHIN scale. That is not a small ask. It would delay rollout by years.

Potential Solutions:

[ASTP / RCE]

- Define a framework for centralized/decentralized consent and authorization services under TEFCA IAS – similar to CSPs.

- Determine if Consent resources could be federated and/or scoped to manage authorization at the network level

[EHR Vendors]

- Implement local consent management options for granular record sharing.

Problem 5: Missing Support for Delegated/Proxy Access or Minors.

Another critical gap in TEFCA IAS is the lack of support for delegated or proxy access.

In the Patient Access API world, proxy access is partially supported through a “patient picker” UI in many EHR portals. In TEFCA IAS, apps can only query for records associated with the exact individual who was verified by the CSP.

That means:

- No access for minors

- No access for dependents

- No caregiver or family proxy access

- No support for patients who cannot complete CSP onboarding by themselves

This is a real-world problem. Authorized caregivers often manage care for people who cannot consent on their own. Those patients may not have the ability to take a selfie or scan an ID. In the physical world, a signed and notarized document can be enough to grant access. TEFCA IAS does not support this pattern at all right now.

Unfortunately this issue is further complicated by the fact that proxy & delegated authority rules vary significantly state-by-state.

Potential Solutions

The issues here are many, some tied to the fact that proxy & delegated authority rules vary significantly state-by-state

[ASTP / RCE]

- Develop national guidance for proxy and delegated access under TEFCA IAS.

- Standardize representation of proxy relationships and legal authority in IAS transactions.

- CSPs may not want to (or be able to) take on the responsibility for validating proxy/delegated authority. This may require the creation of another framework for centralized/decentralized proxy & delegated access management

- Determine if Consent resources could be federated and/or scoped to manage proxy/delegated access at the network level

[CSPs]

- Create verification workflows for authorized delegates and caregivers.

- Support supervised proofing for minors and users unable to complete standard onboarding.

[EHR Vendors]

- Align existing proxy management features (e.g., patient pickers) with TEFCA IAS identity standards. (Only currently possible for EHR vendors leveraging Facilitated FHIR)

Problem 6 - Unrecognizable RLS Responses

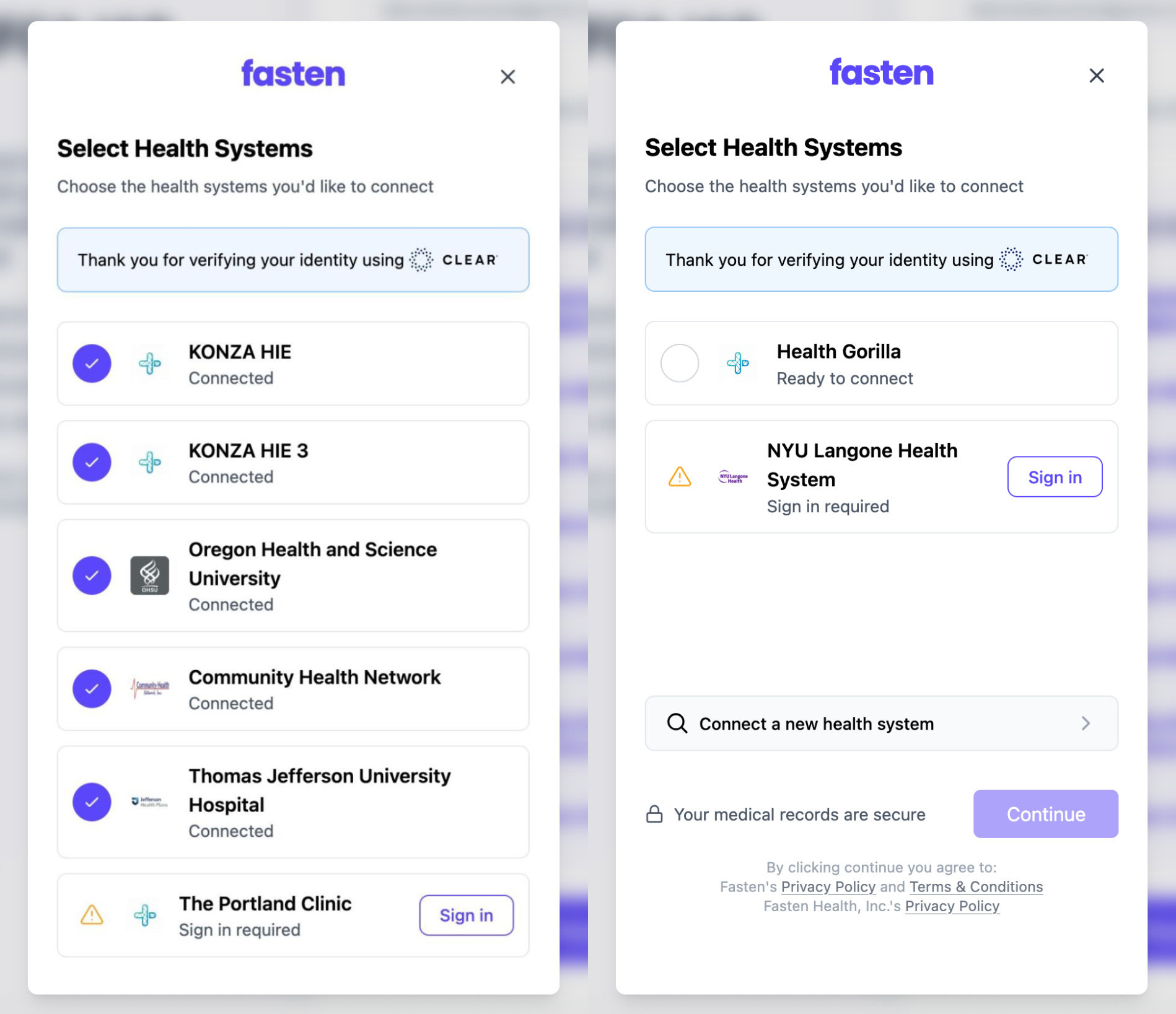

Some QHINs (like Health Gorilla and Konza) seem to respond to RLS requests with limited information. Instead of providing the names of the various healthcare providers on their network who hold a portion of the patient’s record, they instead respond with their own identifier – essentially hiding the name of the actual institution that the patient visited for treatment.

This causes a number of problems, the most obvious of which is the fact that the patient has no idea who “Konza” or “Health Gorilla” are, so they’re likely to consider them unimportant healthcare providers or even suspicious data holders. By aggregating their whole network under one unrecognizable entry, patients lose the ability to meaningfully consent. This is problematic because both of these organizations facilitate medical record exchange for millions of Americans and thousands of healthcare institutions.

[ASTP / RCE]

- Clarify TEFCA policy requiring QHINs to return the actual source institution names (sub-participants) in RLS responses.

[QHINs]

- Include provider names and identifiers in RLS responses instead of masking them with QHIN-level identifiers.

Problem 7 - Lack of Feedback Mechanism & No Transparency

Patients generally recall the important healthcare institutions they have visited, even if they can not remember the exact facility name.

Right now, IAS providers and patients have very little visibility into how the network is behaving.

- There is no standardized way for a patient-facing app to tell if health systems are actively responding to

T-IASrequests- “Hospital X last responded to an IAS request on [date],”

- Patient matching algorithms are a black box.

- Which demographics are being used?

- How are they weighted?

- Are historical names and addresses required, optional, or ignored?

- There is no standard way to explain why a given provider did not return records.

- While there is a directory of TEFCA participants, it doesn’t specify who responds reliably, and who is effectively dark.

While all network participants are required to respond to T-IAS requests, through our TEFCA Network Test we’ve confirmed that there are some institutions that are “live” on the network but are not actually responding to patient requests. This isn’t related to patient-matching algorithms at all – the providers have not enabled T-IAS responses in their EHR.

Potential Solutions

[ASTP / RCE]

- Include IAS response metrics and reliability data in the TEFCA Directory

- Require QHINs to publish standardized response and uptime reports.

Conclusion

If there is a theme running through all of this, it is that there is no single correct answer to all these problems. Patient matching, record discovery, consent, delegated access, reliability reporting – there’s a spectrum of complex tradeoffs that need to be considered when there’s so many stakeholders and patient lives involved. TEFCA IAS has made incredible progress – and the issues we’re discussing are almost expected given the nature of adding “untrusted” participants to an architecture that was previously designed around implicit trust. We’re adding a new layer of functionality to a network design that’s been optimized for over a decade and works already at incredible scale.

We’re confident that TEFCA will work through these knots. The incentives are finally aligning, and the real world is supplying the best possible feedback loop – we’re just one of many voices at this table.

Fasten Health is completely committed to TEFCA, and the potential benefits. We’re moving towards a national network where patients can securely access, share, and control their own records as easily as they can connect their bank accounts today.

Reach out and we can walk through the details, roadmaps, and what this means for your workflows. Or, if you prefer to try it first, sign up for the TEFCA IAS Network Test form and experience the IAS flow for yourself!

Finally, a thanks to everyone who reviewed and gave me feedback on this post:

- Brendan Keeler

- Dave Boerner

- Gene Vestel

- Jim St.Clair

- Pryce Ancona

Developers Need to Know: Which Payers Are Required to Provide API Access?

Developers Need to Know: Which Payers Are Required to Provide API Access?