Over the last few months, I’ve had a number of patients and companies reach out to ask about Fasten and how we fit in with TEFCA Individual Access Services (IAS). On paper, TEFCA seems like the dream solution to interoperability: a single, simple way for patients to access their records, without needing to remember dozens of patient portal passwords. Just verify your identity once, and you’re good to go, right?

That was the promise. The reality? Well, let me tell you a story.

The Promise of TEFCA IAS

Fasten has been keeping a close eye on TEFCA and the Patient Access ecosystem. We’re members of the Sequoia Project Consumer Engagement Workgroup, where we provide feedback from the patient app developer POV. We’re also members of the CARIN Alliance and HL7 Patient Empowerment workgroup.

When TEFCA IAS was first introduced, it sounded like a huge step forward for patient access. The idea was simple: instead of requiring patients to remember which hospital they visited and their portal login credentials, TEFCA would allow them to verify their identity once using a photo of their face and government issued ID (using ID.me, Clear, etc.) and retrieve all their records in one go.

For patients, this would be a game-changer. For Fasten and our customers, this would streamline workflows and increase the number of available records. It seemed like a win-win.

But the reality is not so black & white.

Breach: HIPAA Liability and Patient Records

Let’s take a step back. Under HIPAA, if one hospital mistakenly shares Patient A’s records with another hospital, that hospital won’t consider that to be a reportable breach. Since both entities are covered by HIPAA, they’re expected to securely return or dispose of any misdirected Protected Health Information (PHI) they receive. In most cases, the entity sending the wrong record is likely to conclude that this is a “low probability of compromise” (LoProCo) breach – meaning it doesn’t trigger any mandatory breach notification requirements or the massive fines that might result from a HIPAA breach investigation. Without “low probability of compromise”, national Health Information Exchanges (HIEs) like Carequality wouldn’t be able to exchange over 800 million medical records a month.

But what happens when the incorrect records end up in the hands of a patient instead of another hospital?

Suddenly, a mistake isn’t just a paperwork issue – it’s a full-on HIPAA breach. If John Doe requests his records and gets another John Doe’s records, the health system is now directly liable. That’s why some health systems (and their EHR vendor: Epic) are taking a hardline stance: if a health system can’t guarantee 100% accuracy in patient matching (which, realistically, no system can), they’d rather not take the risk. As a result, Epic still requires patients to authenticate through their health system’s portal—the very problem TEFCA IAS was supposed to fix.

Yet, they’re overlooking a key player in the record exchange – the app developer. As network participants under TEFCA, app developers have reporting obligations and are also required by the TEFCA Common Agreement to comply with HIPAA privacy and security rules, just like doctors and hospitals covered by HIPAA. If they intercept (and securely return or destroy) the misdirected records before they get to the wrong patient,this too could qualify as an unreportable breach under the low-probability of compromise analysis. Further, if app developers follow strict standards for identity proofing of patients - which is required by TEFCA for patient-facing apps - it reduces the risk of a misdirected record.

Health systems & vendors that recognize this – and prioritize both security and the patient experience – are taking a different, more thoughtful, approach. Companies like Meditech and Athena Health have publicly committed to supporting Federated Identity, ensuring that patient access isn’t compromised.

| Vendor | Market Share | IAS Federated Identity Support |

|---|---|---|

| Epic | 37.7% | No (Epic supports Facilitated FHIR SOP) |

| Oracle Health (Cerner) | 21.7% | – |

| Meditech | 13.2% | Yes (100+ customers on Traverse Exchange) |

| Evident (CPSI) | 9% | – |

| Altera Digital Health | 3.4% | – |

| Medhost | 3.3% | – |

| Athena Health | Yes (all sites) |

How can we make this better?

- [HHS] As the CARIN Alliance requested in their comments to the ONC,

we need the the HHS Office of Civil Rights (OCR) to:

“Issu[e] guidance and/or enforcement discretion for situations where an app vendor [that is contractually required to comply with the HIPAA Privacy and Security regulations] reviews or securely destroys non-matches prior to populating them in the wrong patient’s record under the “low probability of compromise” analysis, set forth in 45 CFR §164.402(2).”

By the way, this isn’t a big ask of HHS - in the original HIPAA breach notification rule, OCR already stated in guidance that if information is misdirected to

“another entity governed by the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules…there may be less risk of harm to the individual, since the recipient is obligated to protect the privacy and security of the information …in the same or similar manner as the entity that disclosed the information.” (See 74 Fed. Reg. 42740, at 42744 (Aug. 24, 2009) (emphasis added).)

- [EHRs] We also need other large EHR vendors (looking at you Oracle Cerner) to publicly state they are following Meditech & Athena’s lead, and will be responding to Federated Identity requests directly, rather than requiring a hybrid verified identity AND portal credentials – which is basically the worst of both worlds.

- [Practitioners and Health Systems] should recognize that patients are frustrated with the dozens of portals they have to login to to get their comprehensive medical history. TEFCA IAL2 tokens (more on that later) provide a common, safe and secure mechanism to uniquely identify the patient. If it’s safe enough to use Clear and ID.me to login to government webpages or board my flight, why can’t I use this same mechanism to access my medical data?

- [Fasten] In the meantime, here’s what we’re doing at Fasten:

- We’re prioritizing integrations that make it easier for patients to retrieve their records today – which includes TEFCA’s record locator service – which solves the discoverability problem (answering “which health systems have I been to?”)

- We’re integrating directly with healthcare providers (over 40,000 at last count) in addition to TEFCA. Our goal is to become a turn-key solution for any and all ways for patients (and app developers) to access medical records.

Mandatory Response: HIEs & Treatment Purpose of Use

The next topic that’s crucial to understand is how the existing national Health Information Exchanges (HIEs) relate to TEFCA – and what benefits TEFCA brings along for patients.

HIEs exist to facilitate the exchange of medical records between healthcare organizations – generally without patient involvement. They operate under HIPAA’s allowance for medical record disclosure and sharing for “Treatment,” “Payment”, and “Health Care Operations” (commonly referred to as HIPAA TPO).

There are two key concepts to understand about HIEs:

- Treatment Purpose of Use – Most HIEs only permit record exchange for treatment purposes – providers are directly involved in the treatment or management of care of their patients. While there’s been plenty of words written about whether these networks are (allegedly) used for other purposes, that’s a separate discussion.

- Reciprocity - This is arguably the most valuable feature of the HIE networks. All organizations participating in an HIE network agree to share patient data with each other, allowing any provider within the network to access relevant medical information about a patient, regardless of where they originally received care.

Together, these principles ensure that all treatment-related record requests within the network are mandatory—an incredibly well-thought-out design that enhances interoperability.

Unlike HIEs, which grew organically at the state and municipal levels, TEFCA is a nationwide interoperability framework overseen by the Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy (ASTP) (formerly the ONC).

While HIEs have traditionally focused on provider-to-provider data exchange, TEFCA introduced a transformative new request type for patients: T-IAS. For the first time, patients can query the network directly for their own medical records – something that was generally not possible under HIEs.

This brings us to one of the bright spots in TEFCA: responding to T-IAS requests is mandatory under the Common Agreement. While response rates were initially slow in early 2024 (below 4%), recent estimates suggest a significant improvement to 15-30%, and getting better.

This momentum signals that TEFCA IAS is gaining traction, thanks to the hard work of EHRs, QHINs, the Sequoia Consumer Engagement Workgroup, CARIN Alliance and other patient advocacy groups.

How can we make this better?

- [Practitioners and Health Systems] While responding to TEFCA IAS requests is mandatory, connecting to the network itself is optional in many states. If you’re a practitioner, health system or EHR vendor, you should consider joining the network to improve patient access and interoperability. Patient need their records from all the healthcare institutions they’ve visited, not just the ones that have already joined TEFCA.

Identity Verification Madness

Unfortunately the fantastic growth in the TEFCA network response rate is overshadowed by some of the roadblocks app developers will experience as they attempt to implement the TEFCA IAS Standard Operating Procedure (SOP)

But before we get into all that, lets discuss how identity verification in TEFCA IAS is supposed to work:

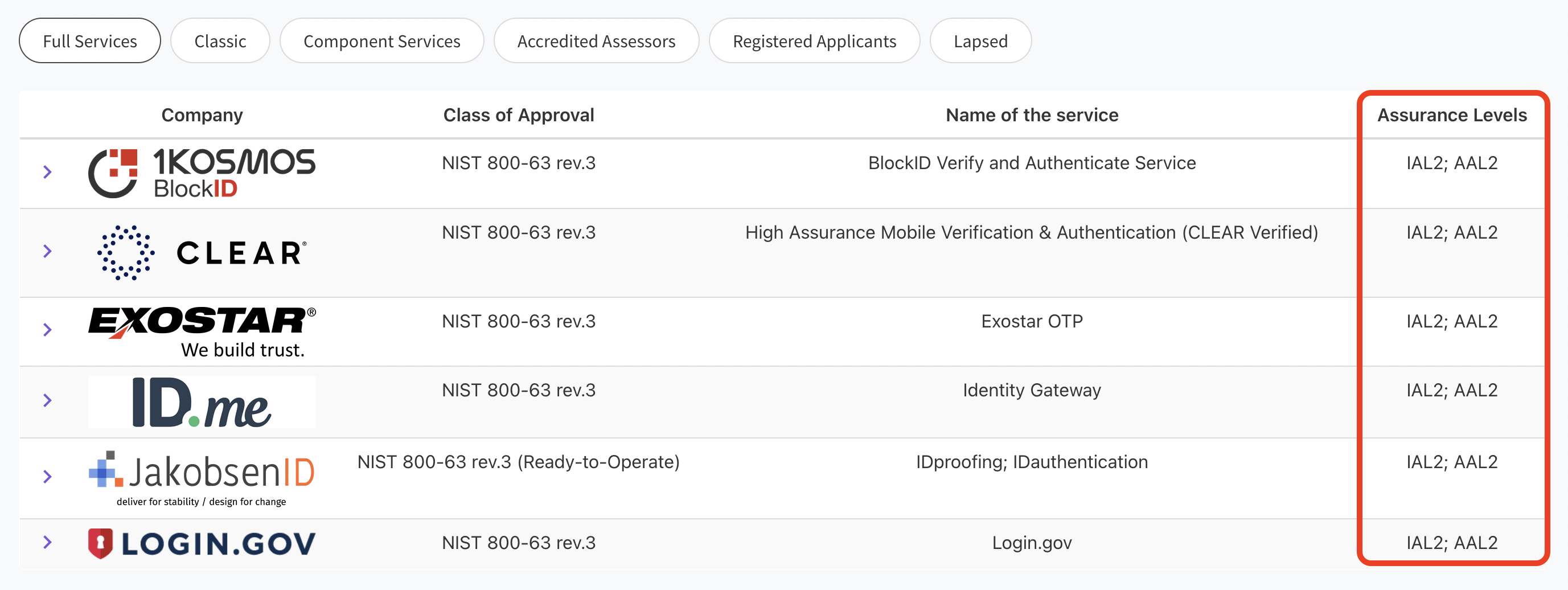

- Application developers select a Qualified Health Information Network (QHIN) they would like to partner with. QHINs are basically on-ramps onto the TEFCA network, and provide APIs and services to developers.

- Next, application developers find a Kantara Initiative certified identity verification/credential service provider (CSP). These are trusted vendors who can verify a patient’s identity using a photo of their face and a copy of their government issued ID, and return a OpenID Connect Token containing verified metadata about the patient.

- Finally, the Application developer must integrate with the QHIN’s API and provide the OpenID Connect Token with each request to the network. The QHIN (and downstream nodes within the network) can then verify the authenticity of the token using a published public key that each identity verification provider makes available.

This sounds straight-forward, to the point where the SOP is only 5 pages long -- but the devil’s in the details.

Missing Federation Requirements in IAS SOP

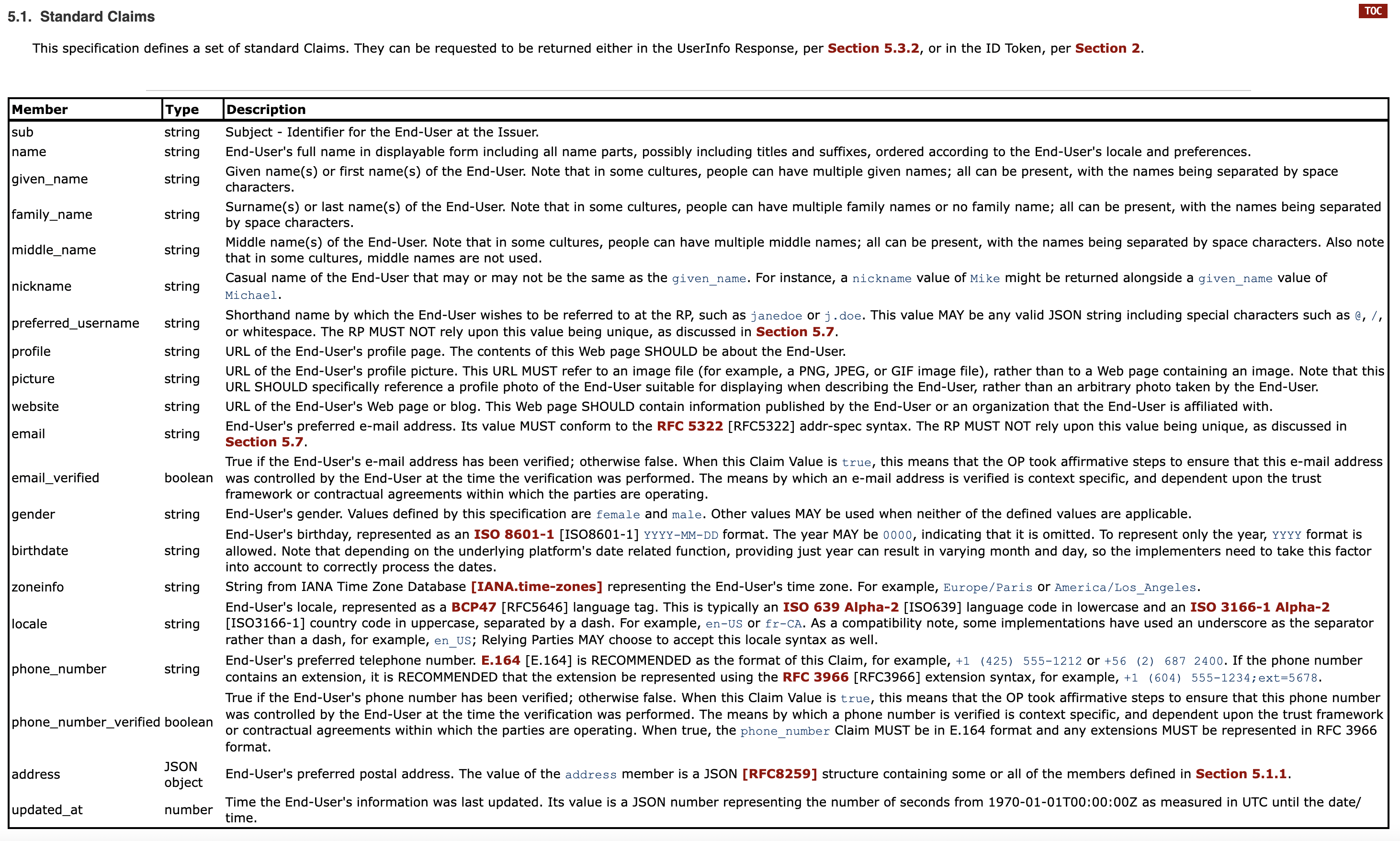

Verifying a patient’s identity isn’t as simple as it sounds. The NIST guidelines are over 250 pages long, and are broken up into 3 sections: proofing, authentication, and federation.

- “proofing” (IAL) refers to the process of verifying a user’s identity against real-world documentation, establishing that they are who they claim to be

- “authentication” (AAL) is the act of confirming a user’s identity by checking their credentials (like a password or biometric) to access a system

- “federation” (FAL) is a system where multiple organizations can share identity information and trust each other’s authentication processes to allow users to access services across different platforms with a single set of credentials

For the purposes of the TEFCA framework, vendors are only explicitly required to provide “proofing” (IAL) and implicitly required to provide “federation” (FAL) services -- they need to verify the patient, and provide a token that can be verified for authenticity by third parties.

But wait a second: the Kantara Initiative only certifies vendors to a specific “proofing” (IAL) or “authentication” level (AAL) – they do not certify any vendors for their “federation” (FAL) levels.

There’s no mention of “federation” (FAL) level on the Kantara website. Worse, because the SOP only describes FAL verification, but does not explicitly state that identity verification vendors must be FAL1 compliant it creates unclear expectations for developers and implementors.

As a developer, you’ll find out the hard way that a large number of the IAL2 vendors certified by the Kantara Initiative are not able to generate an OpenID Connect Token, which means they are effectively unusable for TEFCA IAS purposes.

The following table lists all IAL2 certified vendors, and their support for OIDC Token Generation as of date of writing.

| Kantara Certified IAL2 Vendor | Compliant OIDC Token Generation |

|---|---|

| 1Kosmos | Did not respond |

| Au10Tix | Did not respond |

| Clear | Yes |

| Exostar | Did not respond |

| Experian | Did not respond |

| ID.me | Yes |

| IDDataWeb | Yes* |

| IDEMIA | No |

| Incode | No |

| JakobsenID | Did not respond |

| NextgenID | Did not respond |

| Onfido | Did not respond |

| Persona | No |

| Proof | No |

| Socure | Did not respond |

- [*] manual vendor configuration necessary, does not work out of the box.

(Non)Standard Claims

The basic claims embedded in the OpenID Connect JWT token are standardized in the OpenID Connect Core specification. This means that any identity verification vendor you choose will return the patient’s metadata in a standardized format, which can be verified by QHINs and downstream nodes in the network.

The problem is that the TEFCA IAS SOP does not strictly limit itself to the OIDC standard claims – they want to support additional claims such as Historical Addresses, SSN, Mother’s Maiden Name, Birth Place Address, etc.

Taking a step back, lets remember that there are 3 actors that need to reference and use this OIDC token:

- CSP - Companies like CLEAR generate an OIDC token containing verified information about individual patients

- App Developers/IAS Provider - companies like Fasten use the verified patient information to query TEFCA network (via a QHIN) for a list of healthcare institutions that the patient has previously visited, and request a copy of their records

- QHINs - these TEFCA “on-ramps” help app developers query the network, but they are also responsible for protecting the network from unauthorized access and abuse.

When a CSP generates an OIDC Token, they can technically add any additional data they want, using any field names they deem appropriate. The issue is that non-standard field names are… non-standard – they can be anything. App developers and QHINs may not be looking for them and may not be aware of what the data even means or how to validate it. There needs to be a consistent specification that everyone agrees on.

The Sequoia Project is the Recognized Coordinating Entity (RCE) for TEFCA – they are responsible for defining the foundational standards and specifications that all actors will adhere to when interacting with the network.

When writing the TEFCA IAS SOP, the Sequoia Project leveraged the OpenID Connect Core Standard Claims as a well defined foundation for all identity metadata. But then they introduced a number of mandatory and optional non-standard fields:

- historical_address

- SSN

- SSN_Last_four_digits

- ZIP+4

- Mother’s Maiden Name

- Birth Place

- Birth Place Name

- Principle Care Provider ID

However the referenced non-standard claim names are not well defined. CSPs can name & structure their claims however they like, meaning that app developers and QHINs will be unable to use this additional data in any meaningful way – unless Sequoia, Kantara and the CSPs all agree to some level of consistency.

A good example of this is the SSN field. We’ve seen “ssn”, “ssn9”, “ssn4”, “SSN”, “SSN_Last_four_digits” and others in the wild.

This isn’t technically a blocker for developers, but is definitely an oversight that will cause confusion and limit the number of matching results (eg. historical addresses).

Token Expiration

But by far, the most concerning oversight in the SOP is token expiration.

Recall that each request to the QHIN APIs must include a copy of the OpenID Token. However these JWT tokens expire -- and usually expire incredibly quickly. Most CSPs generate tokens that expire within 5-15 minutes.

It doesn’t make sense to ask the patient to verify their identity to IAL2 (photos of their face and government ID) multiple times in a single session, or even every time they log in. That would be incredibly burdensome, and not the intention of the Sequoia technical leads for the SOP (from my understanding).

But that’s the reality. The spec excluded any mention of token expiration, meaning that the patient will technically be required to verify their identity over and over… and over. It’s a painful experience for patients.

But it doesn’t have to be. In the SMART-on-FHIR (portal authentication) world, developers are given a “refresh_token” which allows them to access APIs on behalf of their patients for months or years, without patient involvement. At the same time, patients always have the ability to revoke their consent at any time. This is the kind of patient experience we should seek to achieve in the IAL2 identity verification world as well.

How can we make this better?

- [Kantara Initiative] Please certify your Identity Services to their IAL, AAL and FAL levels. The ability to generate a token that can be verified by third parties (like QHINs) is a requirement for TEFCA IAS. A list of IAL2 vendors is not sufficient for developers.

- [Identity Verification Providers/CSPs] Please read the TEFCA IAS SOP – it’s only a couple of pages, and they clearly state the requirements for developers leveraging your tokens. An OIDC compliant token + public keys in a JWKS published at a well-known url are all we need. These few requirements open your company up to a whole new market of healthtech companies that will be constantly verifying patient identities.

- [Sequoia Project] Please clarify the TEFCA IAS SOP, making it explicit that OIDC tokens are a requirement for IAS developers, and work with your CSP approval organization (Kantara) to ensure that developers can easily determine which vendors meet the requirements.

- [Sequoia Project] Please provide guidance on how you expect application developers and QHINs to handle expired tokens. What is the patient experience you intend here? If long-lived OIDC tokens are the expectation, the duration should be written into the SOP, and these requirements should roll out onto your CSP approval organization (Kantara).

- [Sequoia Project] Given that you define a number of mandatory and optional non-standard claims in the SOP (eg, historical addresses, SSN, mothers_maiden_name), you should publish your own standard and work with your CSP approval organization (Kantara) to ensure that all CSPs can comply.

- [Sequoia Project] The SOP references “address.regionality” in the spec table, but then uses “address.region” in the example. The official OIDC standard claims (and Carequality HEAT tokens) use “address.region”, which is what we assume the correct field name is. These kinds of ambiguities/editorial oversights are confusing to developers, and cause lots of unnecessary discussions with QHINs and CSPs.

Where Does This Leave Us?

Fasten will support TEFCA IAS – and we’re building as fast as possible to make that happen.

While it’s not perfect, we firmly believe in its potential to completely transform the patient access experience, if the right improvements are made.

At Fasten, we are committed to patient access and patient empowerment -- and that means we’ll do everything we can to make TEFCA IAS better, even if that’s just writing deeply technical blog posts as we run into problems. We want to help create a future where patients can easily access their medical data without any barriers.

Finally, a thanks to everyone who reviewed and gave me feedback on this post:

- Brendan Keeler

- Deven McGraw

- Jill DeGraff

- Josh Mandel

- Ryan Howells

Photo by New England Journal of Medicine

How to Ignore Information Blocking Legislation Like a Pro

How to Ignore Information Blocking Legislation Like a Pro